Polychromy

Information about the use of color in ancient sculpture and modern recolorings

Sculptures in living color

We encounter color every day, everywhere, from billboards and posters to neon signs and social media posts. The ancient world was no different, as is evident from the traces of polychromy, or multiple colors, found covering the surfaces of ancient architecture and sculpture. Bright, eye-catching, and often bordering on what we would consider garish today, ancient civilizations colored their world by applying pigments and dyes to finished stone surfaces.

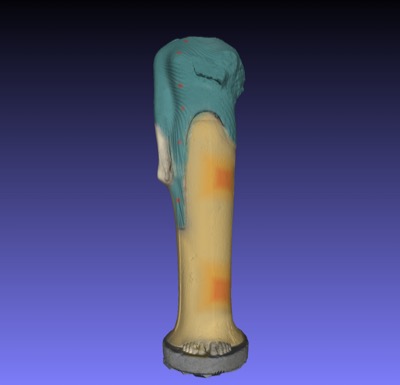

At excavation, bits of color may be visible on artifacts, but surface cleaning and exposure to air and light soon causes the coloring to fade, leaving it invisible to the naked eye. As technology advances, equipment and techniques are developed to identify the presence of polychromy on ancient materials. Some of these techniques include:

- Multispectral Imaging (MSI) – capturing images of the item in question under a variety of lighting set-ups and sources

- Visible Induced Infrared Luminescence (VIL) – a technique using visible and infrared light that makes Egyptian blue (one of the first synthetic pigments) appear to glow in photographs

- UV-Visible Absorption Spectroscopy – this technique measures reflection and absorption of light directed at a specific location on the sculpture. These measurements generate a graph that can be compared to other known reference samples. From this information the exact colors can be deduced.

- Macroscopic X-ray Fluorescence (MA- XRF) – illustrates elements spatial distribution and creates an elemental map

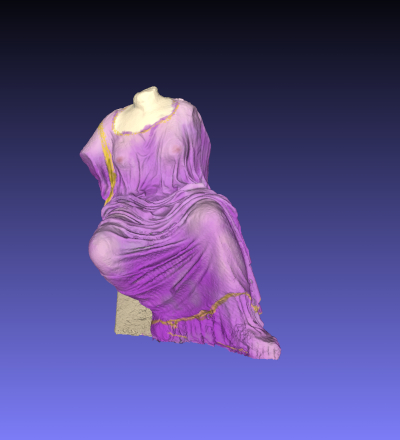

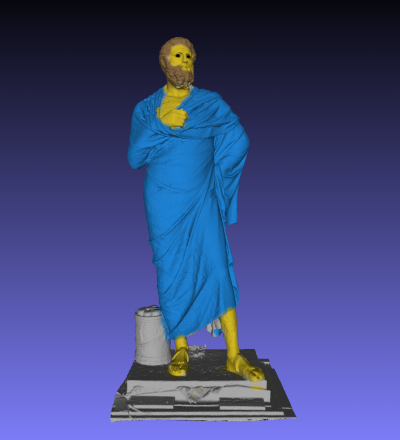

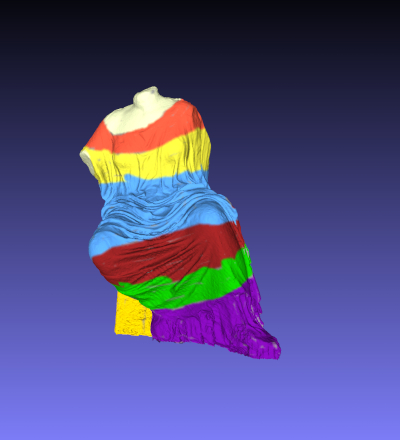

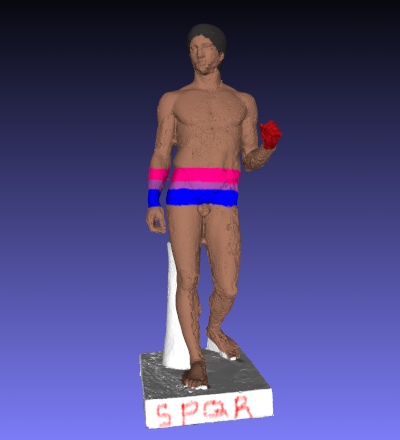

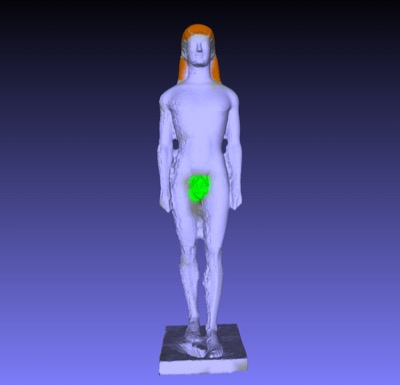

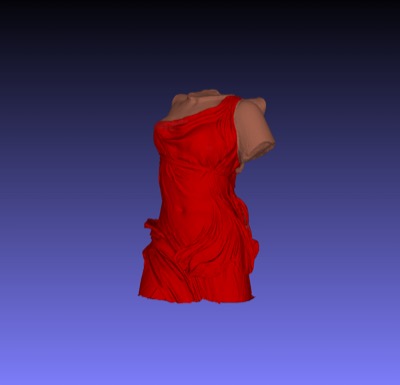

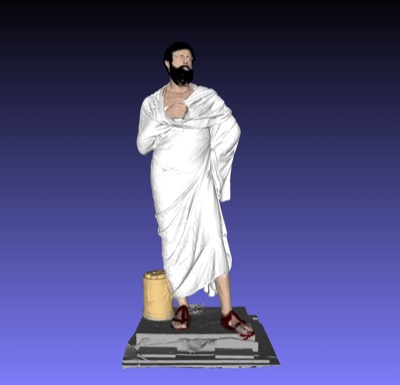

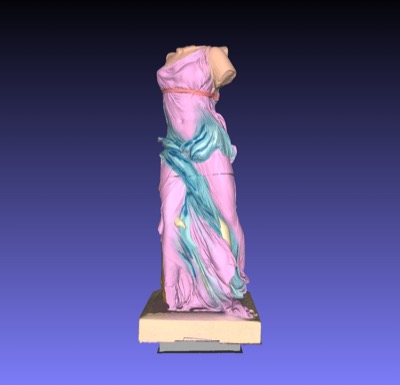

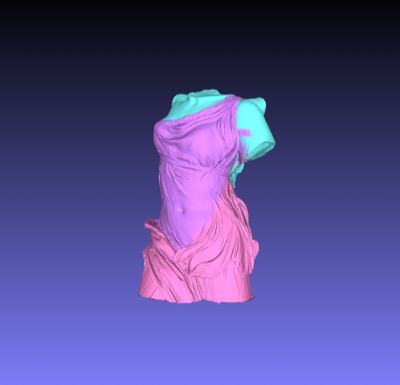

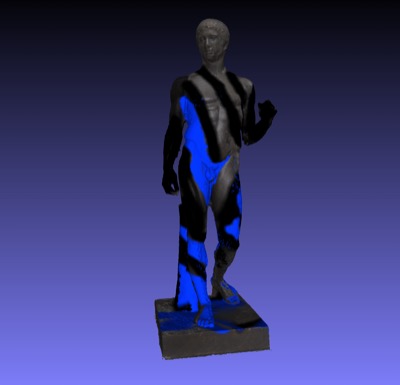

Results from these techniques allow scientists, artists, and art historians to collaborate on the restoration of polychromy to ancient sculpture – their colorful restorations are on replicas rather than the original objects! – and their creations form popular museum exhibits, such as Gods In Color, which has been touring the world since 2003. Uncovering ancient polychromy is a crucial step in correcting popular imaginings of ancient sculpture as pure white. This misconception has wrongly cast the ancient world as devoid of color in both its population and its art, perpetuating the stereotype that white is superior – and this myth of ethnocentric whiteness continues to fuel the argument of white supremacy today.

But where did this myth come from? During the Italian Renaissance ancient sculptures, devoid of obvious polychromy after centuries buried in the dirt, were rediscovered in the course of ground excavation for urban expansion. Sculptors, like Michelangelo, then looked to this newly re-emerged, ancient past for inspiration in their own works. By attempting to recreate what they saw as austere, pure, white ancient art they actually introduced something new to the world: the uncolored sculpture. Later, 18th century German archaeologist and art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who is well known for his volumes on ancient art, claimed white marble statues like the Apollo Belvedere were the epitome of beauty. And modern portrayals of antiquity have done little to halt the misconception: museums and textbooks continue to marginalize color, movies about the ancient world like 300 celebrate xenophobic stereotypes, and only in the last few years have polychrome sculptures begun to reappear in popular media, like video games focused on the past.

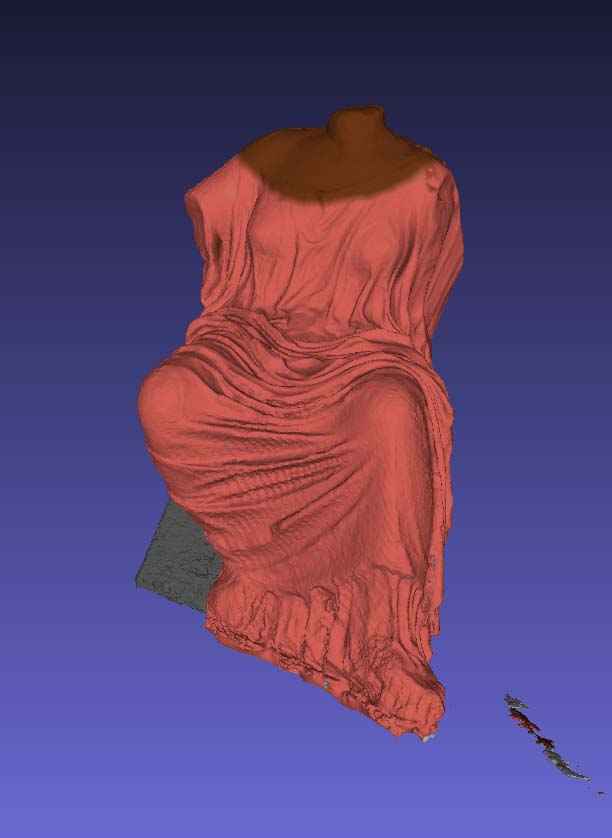

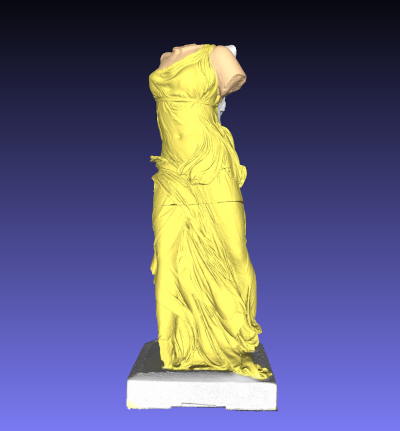

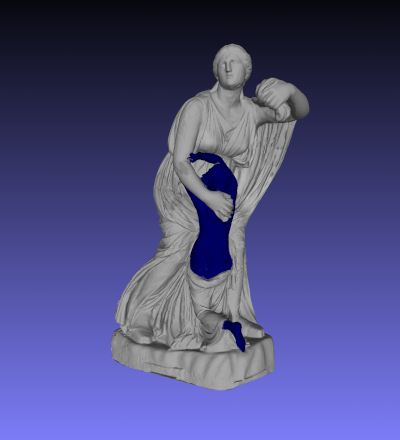

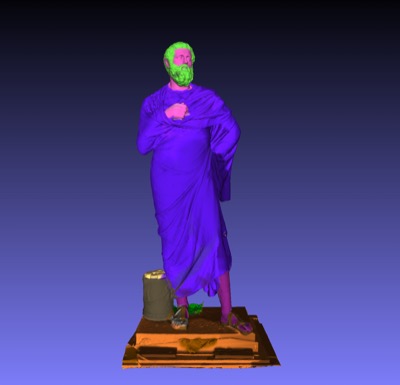

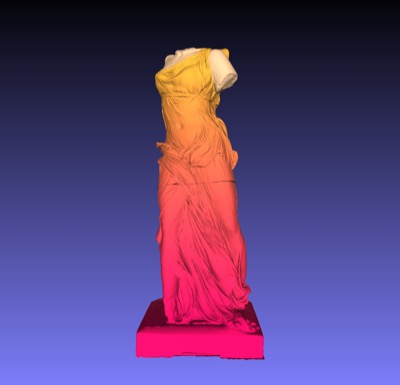

Recently, claims regarding the Greek and Roman roots of Western civilization have been used to bolster white nationalist movements across the United States. The long association between Classical sculpture and the myth of white superiority has provided a basis for some of these arguments, leading professionals in Humanities fields to focus on countering this narrative with alternative perspectives based on historical evidence. Among the most active voices is that of historian Sarah Bond, who has repeatedly emphasized the pervasive role of color in ancient sculpture and the way in which 19th-century scholarship – and practices like cast-making – caused us to see the Classical world as a “white” and “pure” one. Initially such statements provoked backlash among some who thought that this was too political an approach to ancient art, but has since led to an ongoing and productive discussion regarding the place of Classical Antiquity in our view of modern American society. Even modern artists are getting into the discussion: the centerpiece of a recent Jeff Koons installation on the Greek island of Hydra is a brightly-colored sculpture of Apollo holding a kithara and accompanied by an animatronic python. In 2019, the Battle Casts themselves joined the conversation as part of an installation by artist Lily Cox-Richard. The blank, downloadable 3D models created by this project continue the conversation, allowing visitors to paint their own sculptures. You can find links to downloadable models on the individual cast pages and a tutorial on vertex painting on the Learning Resources page.

FEATURED ARTIST:

LILY COX-RICHARD

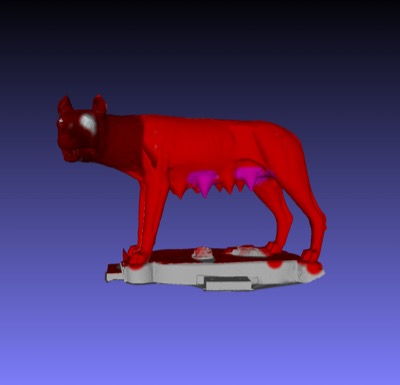

In July 2019 at the Blanton Museum of Art, artist Lily Cox-Richard opened her installation She-Wolf + Lower Figs, featuring a polychrome replica of the Capitoline Wolf sculpture made from digital imaging of the original, as well as several of the Battle Casts wrapped in colorful tulle. Cox-Richard explains that this exhibit was not only an opportunity to challenge the widespread myth of white antiquity, but an opportunity to address questions on the very notions of preference or “taste” — especially of Western taste — in the study of the “classical” legacy. The exhibition received significant media and institutional attention, and the artist has opened new doors for the reuse and adaptation of the casts.