History

Based on its display of Hellenistic emotion and on its stylistic similarities to other Greek sculptures of the period in Asia Minor, the bronze is attributed to the sculptor Epigonos of Pergamon and is believed to have belonged to a monument commemorating the defeat of a Gaulish invasion by this small Hellenistic kingdom. The Gauls were non-Greek, non-Roman inhabitants of western Europe; the Gallic attributes of this figure include the metal torque around his neck, complete nudity, hair spiked up with lye or other substances, and a long mustache. Through the careful working of the collapsing Gaul’s wounds and the evocation of his quiet pain and agony, the Dying Gaul sympathetically represents the humanity of an enemy in the moments before death. Since the marble version’s discovery in the 17th century, the Dying Gaul has been reproduced in engravings, drawings, and sculpture—for the kings of Spain and France, among others—as the classical model for depicting emotion. It was so iconic that Napoleon briefly took the statue from Rome to display at the Louvre.

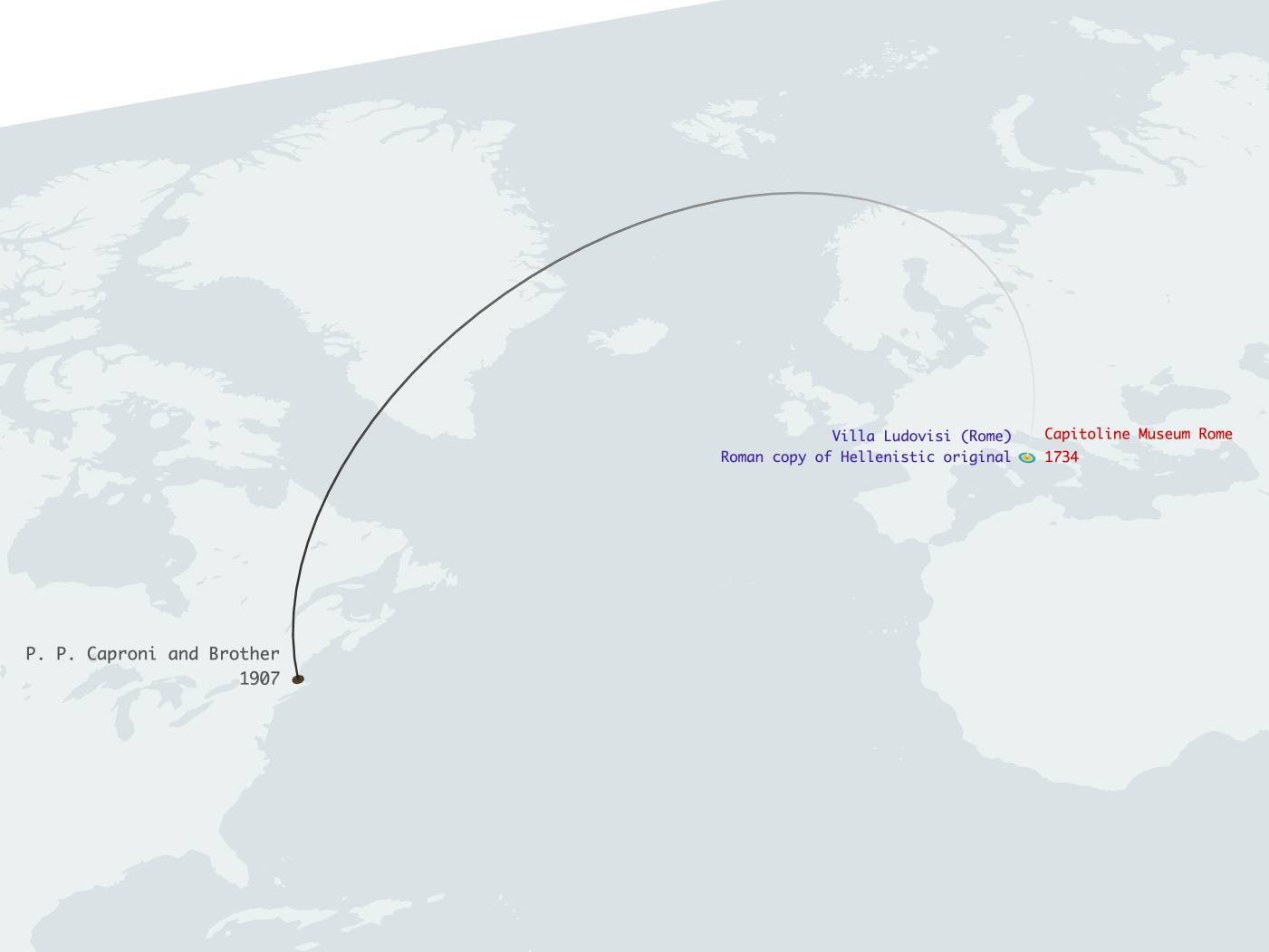

In the summer of 1907, Battle added the cast of the Dying Gaul to his collection where, given its captivating composition in the round, it often became a centerpiece for displays. During UT’s Centennial Exposition in 1936, it anchored one end of a centrally-placed row of Battle’s casts in the Old Library (now Battle Hall) reading room. However, its popularity could not save the cast from claims of inauthenticity; by 1976, when surveyed for conservation, it was in storage at the Pickle Research Campus. Re-emerging for the 1980 opening of UT’s Huntington Art Gallery (now the Harry Ransom Center), the cast once more took up a prominent position in the middle of the gallery floor. It can be seen in this location in a photograph of a group of high school teachers attending a summer seminar funded by the NEH and led by Karl Galinsky in 1983. The seminar introduced the Dying Gaul to discuss ancient society’s changing views of man through the relationship between classical sculpture and text.

In 2006, the Dying Gaul was elevated once more by its installation in the middle of the newly-built Blanton Museum of Art rotunda. In this position it served as a central anchor to unite the surrounding circle of casts reproducing famous sculptures or demonstrating artistic evolution that stood along the outer wall. Today, the Dying Gaul is displayed in the Prints Foyer, where it remains a centerpiece for the cast reliefs lining the walls.